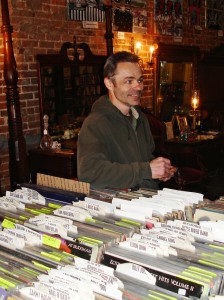

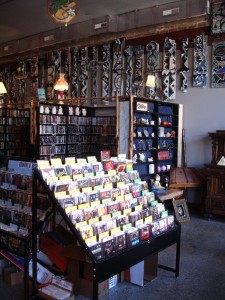

Andrews is located in the outlying western corner of North Carolina, a place far away from major roads and cities—a place that on a map looks like the middle of nowhere. Andrews’ Main Street is a narrow row of aging brick that, apart from a coffee shop and a few thrift stores, mostly houses empty store fronts. But at 982 Main Street you’ll find the space that served as the town movie theater in the fifties and the town soda fountain in the seventies. Today it hosts Dean’s, a specialty record store owned by Dean Williams.

Andrews is located in the outlying western corner of North Carolina, a place far away from major roads and cities—a place that on a map looks like the middle of nowhere. Andrews’ Main Street is a narrow row of aging brick that, apart from a coffee shop and a few thrift stores, mostly houses empty store fronts. But at 982 Main Street you’ll find the space that served as the town movie theater in the fifties and the town soda fountain in the seventies. Today it hosts Dean’s, a specialty record store owned by Dean Williams.

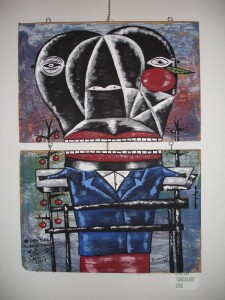

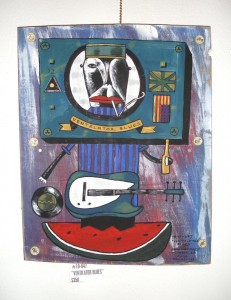

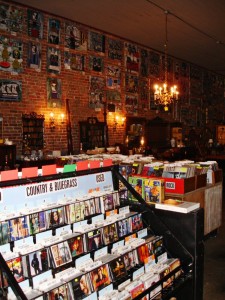

Inside Dean’s you’ll find shelves stacked with CDs and vinyl records, antique furniture and random curios. But most likely your attention will be immediately grabbed by Williams’ artwork, hanging canvas-atop-canvas on the exposed brick walls. Ghoulish faces, serpentine figures nestled in labyrinths of geometric shapes, haunting images of devils and angels, dark wintery woods and olives with eyes that seem to wink at their own inexplicability loom from paintings stacked up to the high ceiling.

A Man About Town

If you try to view Dean Williams as a backwoods novelty or a misplaced artist living in loathed seclusion in a small mountain town, you will misunderstand him entirely.

“A lot of [tourists] are kind of shocked when they first find the shop,” Williams notes of his Andrews location. “They tell me ‘You should be in Asheville!’ And I say ‘If I was in Asheville you wouldn’t have found me.'”

The town of Andrews is very much a part of Williams’ identity and it is clear Williams has no interest in living anywhere else. His family moved to Andrews in 1968 when he was six years old. His wife is a teacher at the elementary school; his eldest daughter lives in the town’s oldest standing house; his storefront has been on Main Street for ten years now; and he’s already bought his cemetery plot.

The town of Andrews is very much a part of Williams’ identity and it is clear Williams has no interest in living anywhere else. His family moved to Andrews in 1968 when he was six years old. His wife is a teacher at the elementary school; his eldest daughter lives in the town’s oldest standing house; his storefront has been on Main Street for ten years now; and he’s already bought his cemetery plot.

Williams began drawing at an early age, a passion he attributes to “dealing with the isolation†of “always being sick in the winter time and stuck in the house.†When he was eighteen Williams began painting. By age nineteen he had sold his first piece and decided to start showing his work. At the time Andrews did not have an art gallery, so in order to have a show Williams says he had to “just make it happen.†His first show hung in the Andrews Public Library.

“I think I just walked in and said ‘Can I hang some art in here sometime?’†Williams recalls.

These days, Williams’ work has been featured in a number of shows throughout western North Carolina. On the day I visit Williams several of his pieces, along with work by his daughter Brittney, are hanging in a show opening that night at the Andrews Valleytown Arts and Historical Society building, one block down from Williams’ store front on Main Street. The building, purchased by the society through grant funding and community donations, was originally a Baptist church, constructed in 1923.

“I really like the idea of one thing becoming another thing,†Williams notes as we tour the space where local artwork is displayed under modern gallery lighting juxtaposed to the high tin ceilings, stained glass windows and wooden railings of the old church. Volunteer staff pace around the space as they set up for the exhibit’s opening night and a fundraising dinner for which they had expected to sell only fifty tickets, though that number quickly doubled.

“I really like the idea of one thing becoming another thing,†Williams notes as we tour the space where local artwork is displayed under modern gallery lighting juxtaposed to the high tin ceilings, stained glass windows and wooden railings of the old church. Volunteer staff pace around the space as they set up for the exhibit’s opening night and a fundraising dinner for which they had expected to sell only fifty tickets, though that number quickly doubled.

Though Williams is clearly happy to participate in the art society fundraiser, by choice many of Williams’ shows have been in less traditional venues such as restaurants and offices.

“I don’t dislike art galleries but I would rather have my work in places where people don’t expect to see original art; whether it’s a blues club or a butcher shop or barber shop, it doesn’t matter,†Williams explains. “I don’t like the idea of art being esteemed as something that can only be in a gallery or a museum. I think it should be where people are on a daily basis.â€

One such place is The Daily Grind, an independently-owned coffee shop, where Brittney works and also has art displayed. Like Dean’s and the art society building, The Daily Grind is another converted space in Andrews’ downtown. At one point it was a body repair shop and splatters of automobile paint still cover the walls along with Williams and Brittney’s paintings.

One such place is The Daily Grind, an independently-owned coffee shop, where Brittney works and also has art displayed. Like Dean’s and the art society building, The Daily Grind is another converted space in Andrews’ downtown. At one point it was a body repair shop and splatters of automobile paint still cover the walls along with Williams and Brittney’s paintings.

“Those two back there are mine,†Brittney says pointing to her canvases as we tour the café. “And the weird African acid-trip looking ones are my dad’s.â€

At age 20, Brittney is a modest and friendly girl her father describes as “a reluctant artist.†She has shown in several shows with her father, but admits she wouldn’t pursue displaying her work without his urging. Many of her subjects are musicians, including Tom Waits, The White Stripes and Ian Curtis whom she depicts in her pieces on display in the old church. Like her dad, Brittney is a prolific and largely self-taught artist. She “took only two years of art classes and hated it,†but produces sketches nearly every day, often during down time at the coffee shop.

“I think she has the same fiber that I have that would never allow her to pursue art in a directed way,†Williams says of his daughter. “It’s more of an organic way where she’ll have to discover it herself.â€

As a young artist in a town where the eighteen-to-twenty-four-year-old demographic is almost nonexistent, Brittney is in a very small minority. She can think of only two other people she went to school with who had any interest in art. Unlike her father, Brittney doesn’t see herself staying in Andrews and may choose to explore a career in tattooing or horror movie make-up. She plans to continue with her art, doing more painting and, like her father, veering away from realistic depictions in favor of what she calls “twists on reality.â€

As a young artist in a town where the eighteen-to-twenty-four-year-old demographic is almost nonexistent, Brittney is in a very small minority. She can think of only two other people she went to school with who had any interest in art. Unlike her father, Brittney doesn’t see herself staying in Andrews and may choose to explore a career in tattooing or horror movie make-up. She plans to continue with her art, doing more painting and, like her father, veering away from realistic depictions in favor of what she calls “twists on reality.â€

“My dad could draw some amazing things that looked like photographs,†Brittney notes. “There was a picture I found of a cowboy that looked so realistic, like he drew every single pore. But now he does olives with faces. I think that’s pretty neat.â€

We’re Out of Peanut Butter

Save the space reserved for works by Brittney, nearly every inch of the record store’s immense walls is covered in Williams’ paintings. In fact, Williams has so many paintings that many more are stored in corners or remain in his old store front until he can find the space for them. He estimates that he’s completed six or seven hundred pieces, sometimes working on several at one time.

Save the space reserved for works by Brittney, nearly every inch of the record store’s immense walls is covered in Williams’ paintings. In fact, Williams has so many paintings that many more are stored in corners or remain in his old store front until he can find the space for them. He estimates that he’s completed six or seven hundred pieces, sometimes working on several at one time.

In many ways, Williams is a paradigm of an outsider artist. He not only didn’t attend art school, he never studied art at all, dropping out of Andrews High in the tenth grade. Instead of using traditional canvases, Williams paints on found materials, particularly plywood scavenged from alleys or donated by friends. Many of his paintings have other found objects attached to them—pieces of wooden knick-knacks, bottle caps, nails, and other reused bric-a-bracs.

“Sometimes I wish I had gone to art school just so I could learn how to manipulate materials, how to use certain techniques,†Williams notes. “But I think it can also be healthy not to have that knowledge. Sometimes making mistakes is a discovery in itself.â€

In contrast to his affable and straight-forward nature in discussing almost anything else, Williams is reluctant to discuss his art, comparing it to the act of ruining a magic trick.

“I find it difficult to talk about my art. Have you noticed that?†Williams says with a laugh. “I don’t like it when someone comes in, looks at my art and says ‘What does this mean?’ My answer is usually ‘What does it mean to you?’ Or when people ask ‘What were you thinking when you did that?’ I don’t know. I might have been thinking ‘We’re out of peanut butter.’â€

Williams doesn’t sketch out most of his paintings ahead of time, but rather “draws with a paint brush†on the canvas. He admits he usually doesn’t know what direction the piece will go.

“I start with eyes a lot,†Williams notes, pointing to a particular canvas where a group of complex geometric shapes are lumped together on a ghoulish face in a surreal version of an eye. “But sometimes my eyes end up being something else entirely.â€

Williams frequently uses the eerie image of coffins, specifically toe-pincher coffins because he “saw them in old cowboy movies†and “liked their shape and wondered about their origin.†Many of his paintings have words or phrases written on them, sometimes discreetly, sometimes prominently, though Williams says he never knows when he’s “going to go that route.†Some of his paintings feature bees, which Williams attributes to a childhood fascination with the creatures. And of course there are the olives, though Williams assures “there is no deep meaning there other than I like olives.â€

African Acid Trip

Though he may be cagey when discussing the meaning of his art, Williams will open up about the greatest influence on his work—music, in particular the blues.

Though he may be cagey when discussing the meaning of his art, Williams will open up about the greatest influence on his work—music, in particular the blues.

“I’m more influenced by music than I am by art or other artists,†Williams says. “I don’t look at other artists that much.â€

As a teenager, Williams discovered the blues through the genre’s influence on rock bands such as The Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin. But growing up in Andrews, Williams music collection was limited to what he could purchase at the five and dime store. There were no record stores in town, and the best place to buy records was twenty minutes away in Murphy, at a bigger dime store.

“Back then, dime stores in small towns just didn’t carry blues records,†Williams recalls. “I discovered blues like most white people did, which is the wrong way. You hear the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin and then find out later that they listened to Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker. In my opinion, the Stones and Zeppelin are great but there’s nothing like the old blues singers.â€

Blues imagery in Williams’ work shows in depictions of sad looking spirits holding guitars and whiskey bottles, through images of juke boxes and vinyl records, and through the lyrics that dance along some of Williams’ canvases. Scribbled on one painting entitled “Bob’s Chicken Neck Blues†are the words “Support blues artists on the Music Maker label†alongside a biblical reference: “And the serpent was crafty.â€

“A lot of people ask me about religious themes,†Williams says. “I’ve never really done religious themes, but I use a lot of religious mythology to make other statements. I do a lot of angels and devils and pitchforks. But that goes back to blues music. That’s a recurring theme in blues music—conflict between good and evil. A lot of blues musicians were told they needed to play gospel music or they would go to hell. To me, gospel and the blues are flip sides of the same coin, like good and evil.â€

Williams’ fascination with the blues led to his fascination with African culture, and his work also shows a heavy influence of traditional African art which can be seen in the shapes of his geometric figures, his preference for abstract rather than realistic depictions, and, Williams points out, his emphasis on faces.

Williams’ fascination with the blues led to his fascination with African culture, and his work also shows a heavy influence of traditional African art which can be seen in the shapes of his geometric figures, his preference for abstract rather than realistic depictions, and, Williams points out, his emphasis on faces.

“That’s why I do a lot of faces and why I don’t do paintings of particular people,†Williams says. “It’s more like painting spirits and occasionally one of them will become somebody.â€

There are other symbols in Williams’ work which he admits are unsettling to some. There are images—fried chicken, beer bottles, watermelons, and pickup trucks to name a few— that could be seen as pejorative depictions of southern culture, particularly African-American southern culture.

“A lot of the themes I do connected with blues music and the whole culture are what people would call stereotypical,†Williams says. “I think it’s sad that people find that insulting. They’ve been trained that if you noticed that black people are different you’re a racist. I don’t see it that way. To me these things are part of the magic of their culture. Just noticing things about a culture doesn’t mean you hate it.â€

Dean’s

Dean’s is the first specialty record store in Andrews and the only one in the surrounding area. A lot of William’s business comes from Murphy and Hayesville, as Williams notes Andrews is not big enough to support the store. Yet despite being smack in the middle of a small town whose Main Street is a testament to the high failure rate of small businesses, Williams’ store is surviving.

Dean’s is the first specialty record store in Andrews and the only one in the surrounding area. A lot of William’s business comes from Murphy and Hayesville, as Williams notes Andrews is not big enough to support the store. Yet despite being smack in the middle of a small town whose Main Street is a testament to the high failure rate of small businesses, Williams’ store is surviving.

This may in part be due to the store’s focus. Williams’ business strategy is to offer things not available at Wal-Mart and other corporate stores. Williams himself attributes the demise of Andrews’ Main Street to Wal-Mart, noting that “it’s almost like they put the ply-wood in the windows themselves.â€

“When I was a teenager, all these stores were full,†Williams notes. “You rarely saw an empty building for any length of time.â€

Dean’s specializes in Afro-beat compilations, vinyl records, and of course, obscure blues albums. Ultimately, Williams store is a specialty blues store, if for no other reason than the blues are where his passion lies and what he most enjoys selling.

“I’m not going to be a fascist as far as dictating what music people can buy,â€Â Williams says. “But what I enjoy the most is selling something that someone buys because they hear it and they like it. If I can turn someone on to John Lee Hooker, I feel like ‘Well, job done for the day.’â€

People come to Dean’s to find records they won’t find anywhere else, and to talk to Williams about the music playing on the store’s stereo, music they probably haven’t heard before. For a time one of these people was the late Mark Linkous of Sparklehorse, who had set up his recording studio, Static King, in Andrews a block away from Dean’s.

People come to Dean’s to find records they won’t find anywhere else, and to talk to Williams about the music playing on the store’s stereo, music they probably haven’t heard before. For a time one of these people was the late Mark Linkous of Sparklehorse, who had set up his recording studio, Static King, in Andrews a block away from Dean’s.

“The first time Mark came in he looked like a guy who had rolled off the back of a bus,†Williams remembers. “He came in and usually I at least try to make eye contact and say hi, but he kind of avoided that. He looked at records for about thirty minutes and then just left. And I thought ‘What a jerk!’ The next time he came in I was playing The Replacements. He said ‘Is that The Replacements? I got to play with them one time.’ I asked ‘Were you in a band?’ and he kind of mumbled ‘Sparklehorse.’â€

Linkous returned to Dean’s from time to time during the years he spent in Andrews, and once brought in Brian Burton, better known by his moniker Danger Mouse, the producer of The Grey Album and one-half of the duo called Gnarls Barkley.

“I didn’t know who he was, but I knew he was special by the way Mark was treating him like royalty,†Williams laughs. “He bought two big stacks of records, the most obscure things I had, things I thought ‘Gee, I’ll never sell this; I should just give it away.’ I saw him in Spin magazine about three weeks after that and thought ‘Oh, I know that guy.’â€

Burton and Linkous recorded parts of their iconic album, Dark Night of the Soul, in Andrews. It was the last album Linkous completed before his suicide in March 2010. Williams shows me the empty building that once housed Static King, speaking of Linkous in the same warm tones he uses when discussing his daughter’s paintings. It’s important to note that though Williams’ affection for Linkous is clear, their acquaintanceship is not something Williams’ has ever publically advertised. There are no signed photographs of Linkous in Dean’s, undoubtedly out of respect to the musician who was known to be private and reserved. Williams’ notes the “last thing†he would have ever wanted to do during Linkous’ time in Andrews was expose him to a fame-thirsty public.

“I got to know him pretty well, but with him being here five years, he was still like a distant stranger,†Williams says. “If somebody else came in [the store] he would find a way to exit pretty quickly. Talking to him was like feeding berries to a deer. If you move too fast, he’s gone.â€

Apart from being a specialty records store, Dean’s has also served as a renegade music venue in a town that Williams emphatically notes “needs more music venues.†Dean’s once hosted a local rock band in need of a place to play, despite lacking the permits required for such an event.

“They asked me if they could play [in front of the store] and I said, ‘Well there’s two ways to do it: we could either find out if we need to get a permit and plan a date for it, or we could do it this Saturday. You’ll probably get shut down but we can just see what happens,†Williams recalls.

“They asked me if they could play [in front of the store] and I said, ‘Well there’s two ways to do it: we could either find out if we need to get a permit and plan a date for it, or we could do it this Saturday. You’ll probably get shut down but we can just see what happens,†Williams recalls.

The band set up, electric guitars and all, on the street in front of Dean’s but were quickly shut down by Andrews police after multiple noise complaints. Realizing lack of a permit only restricted street performance, Williams “pushed the shelves against the walls†and moved the band inside his shop.

“It’s like the Beatles playing on the rooftop,†Williams laughs. “The police thought they were going to harass the Beatles but didn’t realize that’s what they wanted. It would have been kind of boring if the police hadn’t shown up. It was the same here. It made a better story.â€

Everything Is For Sale

Despite the fact that Williams sells most of his paintings through his store, he is reluctant to talk about his art with visitors, admitting that “at least half the time†he lets them leave without saying who created the art on his walls.

“Usually I don’t tell people it’s my art when they come in,†Williams says. “They’ll say ‘Is this a local artist?’ And I’ll say, ‘Well, yeah he’s local.’ I like to be a fly on the wall.â€

It is important to note, should you ever find yourself in Williams’ store, that all the work in the store is for sale—Williams will never hold back a painting out of personal attachment.

“I don’t understand it when I meet artists and they say ‘This one is not for sale; I like it too much.’†Williams says. “If I like something, I want to pass it on more than if I don’t like it.â€

This is perhaps not surprising for a man who favors showing his art in accessible public spaces and loves introducing customers to obscure musicians. For Williams the music he loves is meant to be heard; the art he creates is meant to be seen.

This is perhaps not surprising for a man who favors showing his art in accessible public spaces and loves introducing customers to obscure musicians. For Williams the music he loves is meant to be heard; the art he creates is meant to be seen.

“I’m the same way about records,†Williams says. “There are always going to be records that I want to find, that I want to come across. But once I find them the thrill is gone and I want to pass them on.â€

———

See more of Williams’ extensive catalog of work (as well as works by Brittney) at deanwilliamsart.com… or visit the store at 982 Main Street in Andrews.